| This article was constructed with the help of either writings, lectures or shiurim of Rabbi’s Baruch Dopelt, Berrel Wein, Yossi Bilius, Asher Hurzberg Tzvi Teitlebaum |

The morning sunshine brings with it hope; the presence of a friend can really perk up one’s mood; clarity is a tremendous comfort. If not for these life moments jolting us with positive energy, we might otherwise drown with our sorrows and wither away in our troubles. We need to be comforted, for that is our nature. More so, we have to be proficient in the art of comforting grief, pain, disappointment and loss, for these are all part of every human being’s story. We cannot escape them. It is remarkable how little attention most people pay to the necessity of dealing with misfortune and achieving comfort and consolation. We actively engage in attempts to avoid problems and pain – and correctly so – but deep within our being, we also know that no person escapes tasting the bitter cup, that life always brings with it.

This week’s parsha begins the seven week period of consolation and condolence that bridges the time space between Tisha b’Av and Rosh Hashana. In order to properly prepare for the oncoming year and its challenges, one must first be comforted by the vision of better times ahead and the belief in his ability to somehow overcome those challenges. Healing occurs when he believes that there is a better future ahead. Parashat VaEtchanan always has an upbeat feel to it, since it always falls on Shabbat Nachamu- “Sabbath of Comfort”- taking its name from that week’s haftarah of Isaiah40:1-26, which speaks of comforting the Jewish people about their suffering. Many Jews feel liberated; there are parties, getaway weekends and an all-around joyous time. This however, seems a bit strange, for have we really gotten over our national plight? Judaism considers the comforting of others to be an obligatory commandment – a mitzva. The Talmud points out that God Himself, so to speak, came to comfort Yitzchak after the death of his father, Avraham. Thus our tradition of imitating our Creator, so to speak, naturally encompasses this process of comforting others. When, chas v’shalom, a loved one passes away, we customarily mourn for a twelvemonth mourning period, because to a large extent time heals. G-d gave human beings the gift of forgetfulness. After a while, the sting of loss is not as sharp. G-d allowed one year for the mourner to receive comfort, but at that point it is expected that he pick up his life’s pieces, lick his wounds and move on, tough as it may be. This is apparently not so with our holy temple. We’ve been mourning for it for two thousand years!! Why are we celebrating comfort if we are still in mourning year after year? If for some reason we are comforted, then why do we continue the cycle?

Paysach Krohn tells a touching story that sheds some light on our questions. In the summer of 2000, 16-year-old Mordechai Kaler volunteered to help in the Hebrew Home of Greater Washington in Rockville, Md. One of his responsibilities was to invite residents to attend the daily services (minyan) in the synagogue on the first floor. Some agreed and others refused, but even those who declined did so pleasantly.

There was one man on the second floor, however, who was an exception. He acted nastily and even cursed another volunteer when he was asked to join the minyan. The volunteer was taken aback by the man’s tirade, so Mordechai undertook the challenge of speaking to the angry gentleman.

Mordechai found the man sitting in a wheelchair in a lounge filled with residents of the home. After introducing himself, Mordechai said softly but firmly, “if you don’t wish to join the services we respect that, but why do you curse the volunteer? He is here to help and he was just doing his job.”

“Young man,” the elderly gentleman said sternly, “wheel me to my room. I want to tell you a story.”

When they were alone in the room, the old man told his story of horror, pain and sadness. He came from a prominent religious family in Poland and when he was 12 years old, he and his family were taken to a Nazi concentration camp. They were all killed except for him and his father.

In their barracks there was a man who had smuggled in a tefillin shel rosh, the leather black box containing biblical passages worn on the head during morning prayers. Every day, the men in the barracks would try to seize an opportunity to put on the religious gear, even for a moment, when there were no Nazi S.S. guards nearby. The men knew that they weren’t properly fulfilling the religious duty, as they were missing the hand portion of the tefillin, but their love for doing the Creator’s commands compelled them to do whatever they could.

The man continued, “but for my father that wasn’t enough. My bar mitzvah was coming up and he wanted that at least on that day, I wear a complete set of tefillin. He had heard that in a barracks down the road, a man who had been killed had possessed a complete pair.

“On the morning of my bar mitzvah, my father, at great risk, went out early to the other barracks to get the tefillin. I was waiting by the window with trepidation. In the distance I could see him rushing to get back. As he came closer I could see that he was carrying something cupped in his hands.

“As he got to the barracks, a Nazi stepped out from behind a tree and shot and killed him right before my eyes! When the Nazi left I ran out and took the pouch of tefillin that lay on the ground next to my father’s body and managed to hide it.”

The old man peered angrily at Mordechai and said vehemently, “How can anyone pray to a G-d Who would kill a boy’s father right in front of him? I can’t!”

The man pointed to the dresser against the wall and said, “open the top drawer.”

In the drawer Mordechai saw an old black tefillin pouch, crusted from many years of not being used. “Bring me the pouch, “the man ordered. Mordechai complied.

The man opened it and took out an old pair of tefillin. “This is what my father was carrying on that fateful day. I keep it to show people what my father died for, these dirty black boxes and straps. These were the last things I got from my father.”

Mordechai was stunned. He had no words – no comfort to give. He could only pity the poor man who had lived his life in anger, bitterness and sadness. “I’m sorry,” he finally stammered softly, “I didn’t realize.” Mordechai left the room resolved never to come back to the man again. When he came home that evening, he couldn’t eat or sleep.

He returned to the home the next day, but avoided the old man’s room. A few days later, as Mordechai was helping the men who had come to the synagogue, one of the elderly wanted to recite the prayer said on the anniversary of a death, which requires a quorum of ten.

“I have yahrzeit today and I need to say Kaddish,” the elderly man beseeched. “We only have nine men here today. Do you think you could find a tenth?”

Mordechai had already made his rounds that morning and had been refused by many of the residents. They were either too tired, disinterested or half asleep. The only one he hadn’t approached was the old man on the second floor.

Reluctantly and hesitantly, Mordechai went upstairs. He knew the old man would scold him, but he still had to make an effort. He knocked on the door gently and announced himself.

“It’s you again?” the old man asked.

“I’m so sorry to trouble you,” Mordechai said softly, “but there’s a man in synagogue who needs to say Kaddish today. We need you for a minyan. Would you mind coming just this one time?”

The old man looked up at Mordechai and said, “If I come this time, then you’ll leave me alone?” Mordechai wasn’t expecting that response. “Yes,” he said in a whisper, “I won’t bother you again.”

To this day, Mordechai doesn’t know why he said what he did next. It could have infuriated the old man. But for some reason Mordechai blurted out, “would you like to bring your tefillin?”

Mordechai braced himself for a bitter retort – but instead the man said again, “if I bring them, will you leave me alone? “yes,” Mordechai said, “I will leave you alone.”

“All right,” the man replied, “then wheel me downstairs and make sure that I’m in the back of the synagogue, so I can get out first.”

Mordechai wheeled the old man to the synagogue and brought him to the back. “May I help you?” Mordechai asked as he took the tefillin out of the pouch. The gentleman put out his left hand. Mordechai helped him put on his tefillin and left the synagogue to do other work.

After the services, Mordechai returned to find the synagogue empty – except for the old man. He was still wearing his tefillin and tears were running down his cheeks. “Shall I get a doctor or a nurse?” Mordechai asked.

The man didn’t answer. Instead he was staring down at the straps of the tefillin wrapped on his left arm, caressing them with his right hand and repeating over and over, “Tatte, Tatte [Father, Father], it feels so right.”

The old man then looked up at Mordechai and said, “for the last half hour I’ve felt so connected to my Tatte. I feel as though he has come back to me.”

Mordechai took the man back to his room and as he was about to leave, the old man said, “please come back for me tomorrow.”

And so every morning Mordechai would go to the second floor and the old man would be waiting for him at the elevator holding his tefillin. Mordechai would wheel him into the synagogue where he would sit in the back wearing his tefillin, holding a siddur (prayer book), absorbed in his thoughts.

One morning Mordechai got off the elevator on the second floor, but the man wasn’t there. He hurried to his room, but his bed was empty. Instinctively he became afraid. He ran to the nurses ‘station and asked where the gentleman was – and they told him.

He had been rushed to the hospital the previous afternoon and late in the day he had a stroke and died.

A few days later, Mordechai was given an award by the Jewish home for his work as a volunteer. After the ceremonies a woman approached him and thanked him for all he had done for her. Mordechai had no recollection of this woman. “Excuse me,” he asked, “do I know you?”

“I am the daughter of that man you helped,” she said softly. “He was my father and you did so much for him. You made his last days so comfortable. When he was in the hospital he called me frantically and asked me to bring him his tefillin. He wanted to pray one more time with them. I helped him with his tefillin in the hospital and then he had his stroke. He died wearing them. “This story portrays the contradictory feelings that arise in people. This old man both loved and hated his tefillen, because they were all he had from his father and yet they were responsible for his father’s death.

There is a famous and unusual incident in our Torah pertaining to mourning. When the brothers misled their father Yaakov by telling him that his favorite son Yosef was dead, Yaakov mourned for him continually. He wore sack cloth for twenty-two years until he was informed that Yosef was in fact, alive. Why did he mourn well beyond the customary one year? We are told that the gift of shichicha-forgetfulness did not go into effect. Yaakov’s pain was as clear and as sharp twenty-two years later as it had been on the day he was told of Yosef’s death. Because Yosef was not actually dead, G-d did not implement the usual forgetfulness. In a similar vein, because we have not achieved our ultimate redemption, we still mourn. Unlike a dead relative whom we have lost forever, we will, one day, return from exile. Just as Yaakov’s mourning for the still living Yosef couldn’t be forgotten, neither can we forget the Temple.

Going in a different direction, the Gemara makes an odd statement, that the children of Israel will find comfort through Yishaya the Prophet, though there doesn’t seem to be much comfort in Isaiah. The entire book talks about negativity and rebuke. Where is the comfort? The answer is that when Yishaya was speaking to G-d and acknowledged the children of Israel’s sins, G-d retorted “how dare you speak negatively about my people”. Moreover, G-d punished Yishaya for his statement and Yishaya was killed in battle. The fact that G-d defended us was a tremendous vote of confidence; it’s was a sign of incredible attachment to us. HE is still on our side. HE is still defending His people. He’s saying I’m with you through thick or thin, even though you messed up!! HE’S the protector. This is the greatest comfort our Jewish people can have!!Between these two ideas, we find the answer to our questions. Just as the old man from Paysach Krohn’s story felt both love and hate towards one pair of tefillen, so do we feel both positive and negative about our plight. On the one hand, we are still in galut, without our Temple. On the other hand, we have Hashem’s infinite assurance and support, so we know we will make it to the other side. This idea is expressed in this week’s parsha, when it says “atem hadveikim ba Shem Elokeichem-you who are attached to the Lord your G-d.” The commentaries say that no matter how much a Jew sins, he still is attached to his G-d. He will always possess a yearning for closeness with Him. This stands in contrast to the curse given to the snake: “Your food will be the dust of the earth.” What kind of curse is that? Dust is everywhere; it’s free!! The answer is, that because we have a hard time with our parnasa, it is evident that G-d desires us to get close to Him, as it is specifically in difficult situations that we tend to gravitate towards G-d. The snake gets his food for free and has no need to pray. In essence G-d turned his back on the snake and said, no need to call on Me and no need for Me to call on you. The mood of this almost final portion of the Torah is one of seeming contradictions -sadness on one hand and soaring optimism on the other. Moshe’s sadness is evident in his disappointment about not being able to enter the Land of Israel. His optimism is abundantly evident in his statements regarding the eventual survival and triumph of the Jewish people and the reconciliation of G-d and Israel at the end of days. My Mother, may she live and be well until 120 and have a refuah shelema, has a neighbor who is not religious at all. He was very much a proponent of the physical world and its pleasures. Quite elderly, he still manages to work out and work in his garden. The only time I ever saw him in shul was at my father’s funeral. A number of months ago, he came over to me with a somber look and asked me to pray for his daughter who was diagnosed with a bad machala. He said that for the first time in his life, he prayed to G-d. Astonishingly, he said he had to recollect memories of his kindergarten teacher and the prayers she taught her class. Comfort comes in various ways, but one has to know that it is deeply rooted in attachment to the Master of the universe. When we believe that our ultimate bond is with Him, we will find the optimal comfort.

|

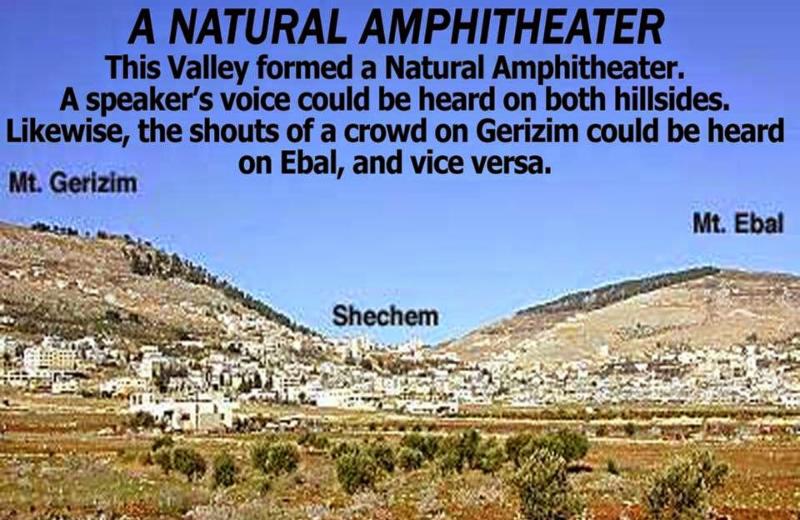

In this week’s parsha, Moshe continues addressing the Israelites just before he passes away and they cross the Jordan River to enter the land of Israel. Moses commands the Israelites to proclaim certain blessings and curses on Mount Grizzim and Mount Ebal, once they reach the land of Israel. Moshe informs them that they can be the recipients of either blessings or curses — blessings if they obey G-d’s commandments, and curses if they do not. According to one interpretation, the location of these mountains is placed outside of Shechem. What is the significance of that city, to the land of Israel initiation ceremony of blessings and curses? Every word in the Hebrew language is not just a label, but the essence of its subject. The word Shechem means segment or portion. Another interpretation understands it as shoulder. These descriptions apply both to Shechem the person and Shechem the place. In essence, these two definitions amount to the same understanding. Each person in Shechem wanted his own portion in life to be significant and not just part of a larger entity. In other words, they each wanted to shoulder the load alone, like a ball hogging basketball star. Shechem was a place that influenced its dwellers and those who traveled through it, to experience a heightened sense of importance and worthiness

In this week’s parsha, Moshe continues addressing the Israelites just before he passes away and they cross the Jordan River to enter the land of Israel. Moses commands the Israelites to proclaim certain blessings and curses on Mount Grizzim and Mount Ebal, once they reach the land of Israel. Moshe informs them that they can be the recipients of either blessings or curses — blessings if they obey G-d’s commandments, and curses if they do not. According to one interpretation, the location of these mountains is placed outside of Shechem. What is the significance of that city, to the land of Israel initiation ceremony of blessings and curses? Every word in the Hebrew language is not just a label, but the essence of its subject. The word Shechem means segment or portion. Another interpretation understands it as shoulder. These descriptions apply both to Shechem the person and Shechem the place. In essence, these two definitions amount to the same understanding. Each person in Shechem wanted his own portion in life to be significant and not just part of a larger entity. In other words, they each wanted to shoulder the load alone, like a ball hogging basketball star. Shechem was a place that influenced its dwellers and those who traveled through it, to experience a heightened sense of importance and worthiness

What’s the difference between a Kabbalist and a Rabbi? A Kabbalist is in a higher tax bracket.

What’s the difference between a Kabbalist and a Rabbi? A Kabbalist is in a higher tax bracket.

There is a story of two brothers who grew up in the slums of New York, in a neighborhood where all young men join gangs. As they rise in status within the gang, they realize the dangers and the essential immorality of their lifestyles. They see all their friends wind up either dead or in jail. Both brothers, against all odds slip through the cracks, taking advantage of opportunities and escaping their neighborhood. They give up their old life.

There is a story of two brothers who grew up in the slums of New York, in a neighborhood where all young men join gangs. As they rise in status within the gang, they realize the dangers and the essential immorality of their lifestyles. They see all their friends wind up either dead or in jail. Both brothers, against all odds slip through the cracks, taking advantage of opportunities and escaping their neighborhood. They give up their old life.

“Shalom” – are we ever going to have peace with the nations of the world, or for that matter, ourselves? It seems very remote; perhaps when Hillary Clinton grows a beard or Donald Trump realizes that he is serving the country and not the country is serving him. Incredibly, even our national identity is being hidden from us. One of the signature symbols of the Jewish nation is the Menorah. We, the Jewish people, have an illustrious and historic past. Miraculously we’ve persevered through thousands of years of persecution and pogroms … just ask your Abba, your Sabbath and Savta, and they’ll tell you firsthand what troubles they’ve encountered. Nonetheless, we can hold our head up high with pride. We have kept our traditions, our culture our commitment to Torah and G-d, well at least some of us, while our past enemies vanished with no trace. However because of the many attacks and invasions over the years against us, of which there have been a few, we have lost many of the physical treasures which symbolizes and stamps our commitment to G-d.

“Shalom” – are we ever going to have peace with the nations of the world, or for that matter, ourselves? It seems very remote; perhaps when Hillary Clinton grows a beard or Donald Trump realizes that he is serving the country and not the country is serving him. Incredibly, even our national identity is being hidden from us. One of the signature symbols of the Jewish nation is the Menorah. We, the Jewish people, have an illustrious and historic past. Miraculously we’ve persevered through thousands of years of persecution and pogroms … just ask your Abba, your Sabbath and Savta, and they’ll tell you firsthand what troubles they’ve encountered. Nonetheless, we can hold our head up high with pride. We have kept our traditions, our culture our commitment to Torah and G-d, well at least some of us, while our past enemies vanished with no trace. However because of the many attacks and invasions over the years against us, of which there have been a few, we have lost many of the physical treasures which symbolizes and stamps our commitment to G-d.

“Be positive, be positive,” blah blah blah. We’ve been hearing that for years. Well, it just so happens that perhaps there are some who don’t wish to take that approach; they don’t feel it’s necessary to put on a façade, a fake smile and feel that the world is shiny bright. As a matter of fact a recent New York Times article, “Tyranny of the Positive Attitude,” reported on a group of psychologists who are attacking the current trend of ‘be positive – be happy’. For several years now, positive thinking has been in vogue. But these good doctors are “worried that we’re not making space for people to feel bad” and feel that a reversal of this trend is in order. There’s been a symposium (“The Overlooked Virtues of Negativity”), a book (Stop Smiling, Start Kvetching), and a push to get psychologists back to doing what they’re supposed to be doing, which is to “focus on mental illness and human failing.”

“Be positive, be positive,” blah blah blah. We’ve been hearing that for years. Well, it just so happens that perhaps there are some who don’t wish to take that approach; they don’t feel it’s necessary to put on a façade, a fake smile and feel that the world is shiny bright. As a matter of fact a recent New York Times article, “Tyranny of the Positive Attitude,” reported on a group of psychologists who are attacking the current trend of ‘be positive – be happy’. For several years now, positive thinking has been in vogue. But these good doctors are “worried that we’re not making space for people to feel bad” and feel that a reversal of this trend is in order. There’s been a symposium (“The Overlooked Virtues of Negativity”), a book (Stop Smiling, Start Kvetching), and a push to get psychologists back to doing what they’re supposed to be doing, which is to “focus on mental illness and human failing.”

One of the most important modern discoveries in the rapidly expanding field of Positive Psychology is recognition of the benefits of gratitude. Much evidence has shown the power gratitude has to make people happier, mentally stronger, and more appreciative of what they have. Research has shown that the simple activity of writing down at the end of each day five things for which one is grateful for has the ability to reduce depression, increase happiness, and improve relationships more than any other positive psychology treatment or technique. College students who consistently exercise gratitude showed to have higher GPAs and better wellbeing. People who actively engage in gratitude practices show better signs of physical and mental health as well as improved relationships.

One of the most important modern discoveries in the rapidly expanding field of Positive Psychology is recognition of the benefits of gratitude. Much evidence has shown the power gratitude has to make people happier, mentally stronger, and more appreciative of what they have. Research has shown that the simple activity of writing down at the end of each day five things for which one is grateful for has the ability to reduce depression, increase happiness, and improve relationships more than any other positive psychology treatment or technique. College students who consistently exercise gratitude showed to have higher GPAs and better wellbeing. People who actively engage in gratitude practices show better signs of physical and mental health as well as improved relationships.

Timna, the mother of Amalek, was the concubine of Elifaz, the son of Eisav. One may find it odd that she was merely a concubine considering she was the daughter of a king and the sister of a prominent figure, Liytan. The reason for this was because she was under the strong belief of ‘better rather be a mistress to this nation than a queen to a different nation’, ‘this nation’ referring to Avraham and his children. In fact, she made her overtures to be the wife of Avraham, Isaac, and Yaakov but was rejected by all three; our forefathers did not accept her. So she settled for Elifaz. In a statement from Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz, which this dvar Torah is based from, he says the bitterness of being rejected by our ancestors became ingrained and transferred to Timna’s future genealogy. The rage Amalek has towards us stems from jealousy of Timna, that of being tossed away and not accepted. Rav Chaim asks “How can that be? It’s out of character of the persona and philosophy of Avraham. This is the great Avraham, whose teachings of G-d and the notion of bringing people back was his virtue. He was an expert of bringing people closer to G-d, to convert everybody and to take them under the wing of glory. The self-sacrifice he gave towards outreach is one of astonishment, and yet he turns and rejects an individual soul who understands the prominence and value of his family, and is willing to give up so much to be a part of it. One can say it’s very commendable on her part. The question remains, ‘Why didn’t they accept Timna?'”

Timna, the mother of Amalek, was the concubine of Elifaz, the son of Eisav. One may find it odd that she was merely a concubine considering she was the daughter of a king and the sister of a prominent figure, Liytan. The reason for this was because she was under the strong belief of ‘better rather be a mistress to this nation than a queen to a different nation’, ‘this nation’ referring to Avraham and his children. In fact, she made her overtures to be the wife of Avraham, Isaac, and Yaakov but was rejected by all three; our forefathers did not accept her. So she settled for Elifaz. In a statement from Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz, which this dvar Torah is based from, he says the bitterness of being rejected by our ancestors became ingrained and transferred to Timna’s future genealogy. The rage Amalek has towards us stems from jealousy of Timna, that of being tossed away and not accepted. Rav Chaim asks “How can that be? It’s out of character of the persona and philosophy of Avraham. This is the great Avraham, whose teachings of G-d and the notion of bringing people back was his virtue. He was an expert of bringing people closer to G-d, to convert everybody and to take them under the wing of glory. The self-sacrifice he gave towards outreach is one of astonishment, and yet he turns and rejects an individual soul who understands the prominence and value of his family, and is willing to give up so much to be a part of it. One can say it’s very commendable on her part. The question remains, ‘Why didn’t they accept Timna?'”